My PhD research paper, hot off the press

And how I used it to speak up against censorship in the scientific community

Dear readers,

This post about my PhD research at Caltech has been a long time coming. Below, I’ll briefly describe the research I spent six-plus years of my life on (officially published January 3, 2025 in eLife!). I’ll also discuss how I publicly spoke out against eLife’s termination of their editor-in-chief last year for expressing pro-Palestine sentiments on social media, and the pushback I faced when making my statement.

Before we dive in, let’s talk about the Eaton Fire, the most devastating fire in Southern California history. Large areas of Pasadena, where Caltech is located, have been evacuated, and the neighboring city of Altadena—a historically Black community—is all but destroyed.

If you would like to help, here are a couple of places I have donated to support recovery:

The UAW Region 6 hardship fund for those impacted by LA wildfires. Caltech graduate students and postdocs are members of UAW Region 6 and those who have lost their homes or other essential resources can get financial support through this fund.

Caltech is located on the traditional, ancestral and unceded territory of the Gabrielino/Tongva peoples. The Eaton Fire severely damaged the Tongva Taraxat Paxaavxa Conservancy. Your donations here will support their restoration and community aid.

Speaking up against censorship in the scientific community

If you navigate to my research paper, published two weeks ago in eLife, you’ll see that the title is highlighted in blue to indicate that it has been annotated with a comment:

My comment reads as follows.

A note from the first author: We received our paper reviews during the week the eLife Board of Directors fired Mike Eisen as editor-in-chief, following his public expression of personal opinions on the Israel-Palestine conflict. I applaud the editors who stepped down to protest eLife's decision and condemn the silencing effect it has had on researchers who fear the professional repercussions of exercising their rights to free speech. This statement is my own and should not be assumed to reflect the opinions of my coauthors.

If you’d like to learn more about the incident that led to Mike Eisen’s termination, and the aftermath, you can read this open letter of dissent, signed by over 2,000 academics before the form closed. I was particularly moved by this paragraph:

It's already apparent that a move to displace Eisen from his role will have ramifications beyond eLife and HHMI. Many of us have received private communications from graduate students, postdocs, and faculty members working at institutions in the USA describing the vulnerability they feel either because they support Palestinian human rights, or because of their Middle Eastern ethnic backgrounds. Many of them have mentioned the backlash against Eisen as a primary reason for their fears. For example, one trainee wrote: “after seeing what happened to Michael Eisen I am extremely worried about my career trajectory and future in the United States... I don’t feel safe as a Middle Eastern neuroscientist in the United States.”

My comment may seem insignificant in the broader conversation and my phrasing is vague. Even so, I had to fight for many months and burn some professional bridges to post it. I refused to proceed with paper revisions and publication of my paper in eLife unless I could express my dissent in a way that was visibly attached to the paper. I also communicated my willingness to start the publication process over by submitting the paper to a different journal. After almost half a year of negotiations, I received reassurance in writing that I could annotate the final eLife paper with this comment and no one would try to get it taken down. Satisfied, I began to work on the paper revisions.

It is worth noting that the powers that be at eLife were very supportive of my desire to publicly express my opinions in this manner. The pushback I received came from Caltech, HHMI, and my coauthors.

The surprising amount of resistance I faced reassures me that my small act of dissent is meaningful. Notch signaling is a tight-knit scientific community, and I’ve gotten to know many of these researchers at Notch conferences over the years, including a conference I co-chaired. My colleagues will see this comment on my paper, and they’ll know how I feel about the genocide Israel is carrying out in occupied Palestine, using US taxpayer dollars. When people say it was “unprofessional” of me to bring that conversation into my professional space, what I hear is that they feel threatened by my audacity. And that means my action was not insignificant.

However, I’m not sure what choice I would have made if I had wanted to continue pursuing a research career. The reality is that I was in a position of unique safety and power. Because I was changing careers, my professional pursuits did not critically depend on my relationships with a few former colleagues. I had already graduated, so my PhD degree was not at stake. I could not be fired, because I wasn’t being paid to do paper revisions. And I had leverage—my coauthors were on the hook to publish the research our funding agencies sponsored, and the revisions could not be completed without my particular skills and knowledge.

Solo protests like mine can make a small difference, but they are not the answer. Collective action brings safety in numbers and much greater leverage. The actions of various Labor 4 Palestine groups and the student encampments last year have amplified this conversation in professional spaces to an unprecedented volume.

This is all to say: get to know your colleagues and neighbors and talk with them about the issues that matter to you. That’s how real change begins. I wrote more about how to organize for change where you live, work, or study in my November post.

And now, for those curious about the actual science in my paper, here’s an accessible overview.

My PhD research: stem cell linguistics

English speech, Arabic script, Chinese Sign Language, Silbo Gomero whistling… and Notch signaling. Our cells have their own languages, and they’re spoken via the medium of molecules. For my PhD research, I studied stem cell linguistics—specifically, how the meaning of different Notch signaling molecules depends on context.

I sometimes joke that studying a stem cell language feels like studying an alien language. I’m pretty sure this is why I was selected to talk at Bubonicon last summer on a panel about Alien Contact—with the legendary sci-fi writer Connie Willis!—despite the fact that I haven’t yet published any fiction featuring aliens. (Although, just you wait… The Ghosts of Gadolin has a few awesome alien languages; learn more about that not-yet-published novel here.)

In the language I studied, the Notch signaling pathway, there are only a handful of “words,” called ligands. These ligands are protein molecules embedded in and protruding from the cell membrane (the cell’s container), and when they bind to other proteins called receptors, Notch signaling occurs. These receptors are also embedded in cell membranes, so cells must be in close contact to communicate using Notch signaling, unlike some other signaling pathways that use free-floating ligands. Think of it like whispering or passing notes in class, as opposed to shouting over a distance.

In addition to speaking to their neighbors, cells can sometimes talk to themselves, just like me when I’m alone in the house (Rachael, it’s really time to do the laundry—just do it, Rachael!). This is called “cis-activation.” Cells can also block themselves from listening in a mode called “cis-inhibition,” which is akin to plugging their ears and singing “La la la la.”

So what do these ligand “words” mean to the cells? What information do they carry? The ligands are instructions for how strong Notch signaling should be. The strength of signaling in turn controls the “listening” cell’s identity.

Notch signaling is kept at a strong level in stem cells, which have the potential to become many other types of cells. When you get injured and your body needs to regenerate the damaged tissue, Notch ligands are used to send instructions to the stem cells:

The first command is to reduce Notch signaling to an intermediate level, which causes stem cells to make many copies of themselves.

The second command is to turn Notch signaling off, which permits the stem cells to be differentiated into e.g., mature skin cells that will replace the ones you had lost.

The meanings of individual ligands (“words”) are contextual

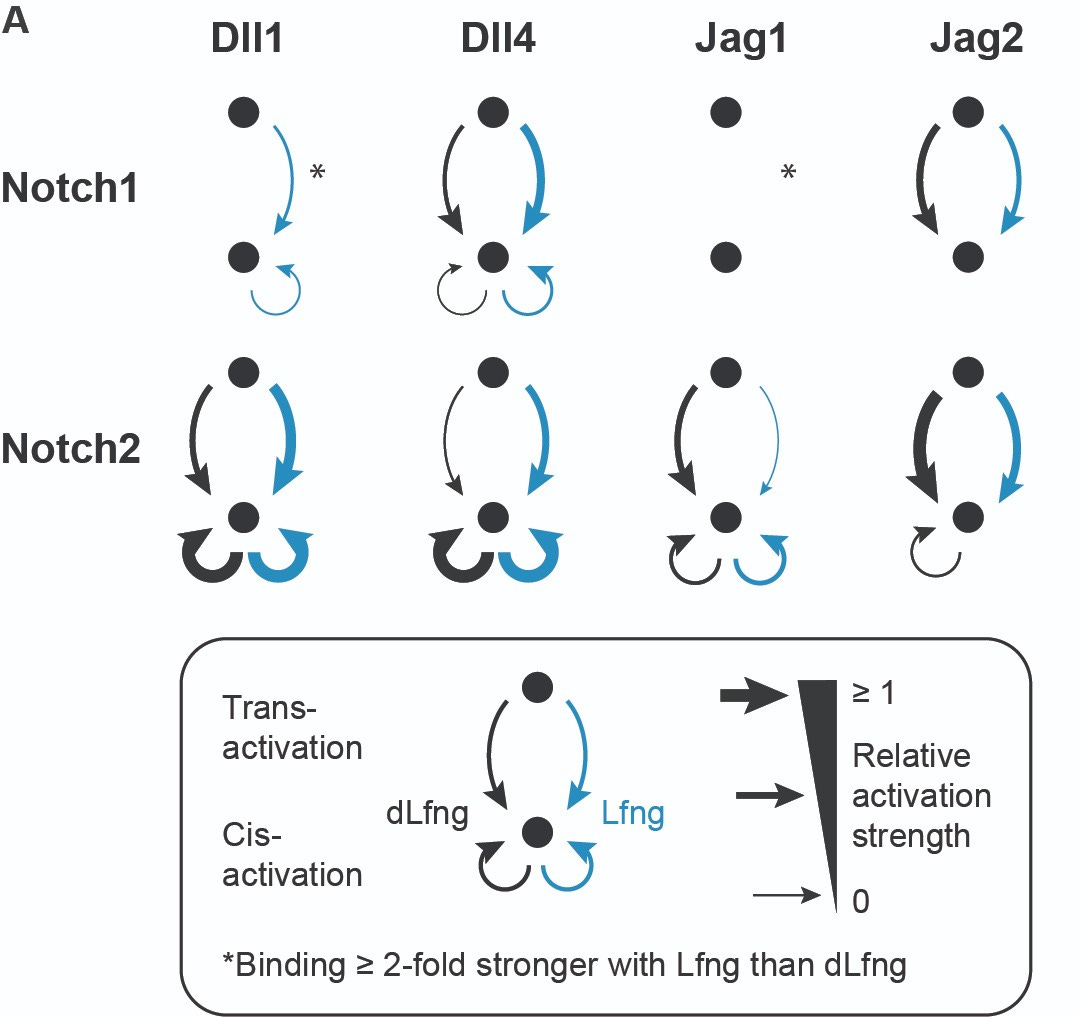

My work demonstrated that when a cell tries to talk to a neighboring cell via Notch signaling, a ligand’s meaning (or activation strength) depends on what receptor is present, what Fringe enzymes are present, and the identity of any ligands that might be cis-inhibiting that receptor.

Here is the map of ligand-receptor signaling strengths that my work defined:

Below is another way to view the same-cell linguistics results (how a cell talks to itself or plugs its ears). All ligands cis-activate the Notch1 receptor weakly and cis-inhibit it strongly when the Notch1 receptor is in the same cell as the ligands. The same goes for the Jag1 and Jag2 ligands with the Notch2 receptors. However, Dll1 and Dll4 activate Notch2 strongly when these ligands are in the same cell as the receptor.

An analogy to describe one of the most interesting conclusions from my paper

Sometimes the meanings of English words depend on context. Let’s take the word “stop,” for example.

If you are annoying someone and they say “Stop!” — they are asking you to cease the annoying behavior.

If you are complimenting someone, and they smile and turn their face to the side while saying “Stop” — it actually means the opposite. They are asking you to keep the compliments coming.

The Jag1 ligand is like the word “Stop.” If the listening cell has the Notch1 receptor, Jag1 really means stop—it efficiently binds the receptor without activating it, which causes Notch signaling to cease. However, if the listening cell has the Notch2 receptor, Jag1 means the opposite—it efficiently activates the receptor, which increases Notch signaling.

If you want to read more, here’s where you can find my paper:

Kuintzle, R., Santat, L. A., & Elowitz, M. B. (2025). Diversity in Notch ligand-receptor signaling interactions. eLife, 12, RP91422. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.91422.3

For those curious about how my substitute teaching is going, the short answer is I still spend most of my time writing so I’ve only had two days in the classroom so far—but they’ve been awesome. Stay tuned for more on that later!

Till next month…

Love,

Rachael

Cool and important research, whether or not you've moved on.

Kudos for standing up!

"They are asking you to keep the compliments coming."

Not necessarily! I've never even seen it in that way. They could genuinely find discomfort in compliments, and/or in a concern over seeming immodest, and could genuinely mean "stop". But I suppose some do it the way you've described, so it's nevertheless a apropos example for this context.

Cool research! Differentiation is so important a process to understand.